Photo by Jason Strull on Unsplash. Monkeys generated by AI.

I’ve been having a bad streak of product launches lately.

My last three products all followed the same pattern. First, I get excited about an idea. Then—in a frenzied sprint—I build an MVP. Then I launch and…no one cares. So, discouraged, I convince myself that the whole thing was a bad idea and move on.

That feeling at the end—the one that tells me to give up—is now so familiar that I’ve given it a name: my quit monkey.

My imaginary quit monkey. He’s not always the nicest.

We all have a quit monkey. He’s the voice in your head saying “you’ll never be good enough”, “none of your ideas are original”, and “your project is doomed to fail”. Our quit monkeys get particularly worked up every time we try something that scares us.

Thankfully, he’s not the only monkey hanging around in my head. There’s another voice—I call him my grit monkey—that balances him out. The grit monkey says helpful things like “don’t give up so easily”, “you got this” and “success takes persistence, you know.”

My grit monkey is more encouraging.

Whenever I try anything hard, my two monkeys start fighting—my quit monkey telling me to give up, and my grit monkey encouraging me to push through. And I never know which monkey to listen to.

Now, if you read inspirational quotes, you might think you should always listen to grit monkey. After all, “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” and “genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” Consensus says that if you haven’t achieved success you just haven’t tried hard enough. All you need is enough persistence—enough grit—to power through the times of doubt.

And this is often true! Many good things in life are difficult, and lots of people give up on things too quickly. But it’s also sometimes nonsense. Yes, sometimes you quit things when you should have persisted, but you can also spend way too long on things that will never succeed. I could dedicate the rest of my life to becoming a world-class surfer, but my 40-year-old, rapidly-decaying body has other plans for me.

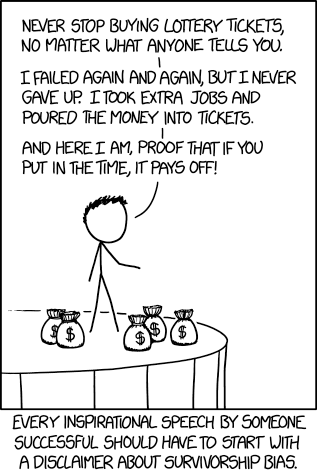

In the startup world, chasing a product idea that is fundamentally flawed will fail, no matter how hard you persist. Sometimes the quit monkey speaks truth.

Sometimes quitting is the right thing to do. Source: xkcd.

So what’s the right way to handle the competing messages from these two monkeys? How do we know which one to listen to and which one to ignore?

If you could predict the future, the answer would be easy: quit everything that was doomed to fail, and grit out everything destined for success. Unfortunately, we can’t predict the future, so we’re forced to make an informed guess.

Deciding whether to quit or grit out each project has been one of the most consistent challenges of my journey as an entrepreneur.

Here are a few strategies that have helped.

Start things slowly

If it was possible to know that you’d eventually quit something then you’d want to quit as early as possible. Every day you don’t quit is a day you’ve wasted doing the wrong thing.

The most efficient way to quit dead-end projects is to not start them.

When I think about all my recent product flops one common trait jumps out: I dove in quickly. They all went from idea to execution in a very short period—usually weeks. And this can be a good thing. After all, inspiration is perishable.

The problem with jumping right into an idea is that you can’t trust how you feel about it. Just like relationships, ideas have a honeymoon phase where everything seems perfect. And like with relationships, the honeymoon phase of an idea isn’t representative of reality—it’s a distorted, rosy, best-possible version of itself. The idea could be the one you want to spend your life with, but it could also be that awkward redhead you fell for in your 20’s that ended up stealing your turtle.1 Like partners, it’s only after you’ve sat with an idea for a while that you can get to know its flaws, and decide if it’s really a keeper.

Only sticking around for the honeymoon phase of your ideas results in continuously moving onto new things—a.k.a. shiny object syndrome. Source: Loryn Brantz.

As a maker, the best way to take an idea slowly is to not allow yourself to build it. Let yourself think about it, research it, discuss it, validate it—just don’t build. Because once you start building, you’ll get caught up in the building and ignore all the other problems with the idea itself.2

Not building also helps you avoid a common grit monkey trap: the sunk cost fallacy. Once you’ve invested heavily in your idea it will be much harder to quit—even if you should.

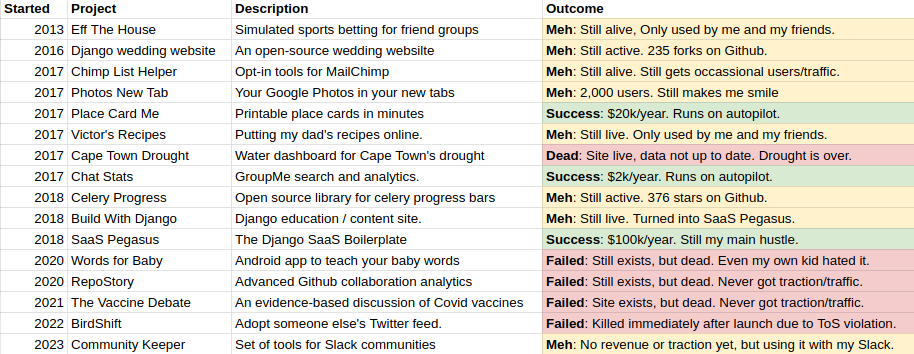

This strategy is how I approached my most successful product: my Django SaaS Boilerplate, SaaS Pegasus. Unlike my recent failures, I spent years thinking about and validating Pegasus before I started building it. I challenged the idea from all angles, talked to potential customers, spun up a marketing site, etc.

Because of all that pre-work, by the time I finally started building Pegasus, I was quite confident it would work. My grit monkey was the strongest he’s ever been. And so, even when building Pegasus turned out to be much, much harder than I expected,3 I could easily push through.

Argue with your quit monkey

There are good reasons to quit something and there are bad ones. Hate what you’re doing? Good reason. Launch went nowhere? Bad reason.

Unfortunately, your quit monkey often can’t tell the difference between good reasons and bad ones. So you have to debate him.

Many quit monkey arguments stem from insecurity, and the bad ones don’t stand up to scrutiny. So interrogate them. If your quit monkey says something won’t work, make him explain why. If the answer is specific—like a technical hurdle, or a killer competitor—you’ll have to drill deeper and see if it can be overcome. But don’t just assume he’s right without putting up a fight.

When my very first product—a wedding place card template—failed to generate any money after several months, my quit monkey started screaming at me. “This project is dumb,” he said. “It’s time to move on.” So we had a conversation. I wrote out every reason I could think of why the business still wasn’t working, and, after interrogating them all, decided none of them were valid. I redoubled my efforts on marketing, and ended up making my first dollar just a few weeks later. The site went on to become my first successful business.

Take a break

Usually quit monkey arguments won’t be clear-cut. Does discovering a big, powerful competitor kill you? Maybe. Or maybe you can out-product, out-market, or out-niche them. These will be judgment calls.

If you’re on the fence about quitting, try taking a break. Breaks are easier to swallow. They’re less permanent—and are less likely to make you feel like a failure.

The most useful part of a break is perspective. Sometimes once you’re out of the throes of working on something you realize that it wasn’t healthy or interesting, and will feel good about leaving it behind. Other times, you’ll find the project continues to pull at you, and you’ll pick it back up. Either way, you’ll see things more clearly after getting some space.

Of the 20-ish projects I’ve made in the last decade, only three have been successful, but most of them still exist. This is because I default to putting things on pause instead of shutting them down.4

Lower your expectations

The more ambitious you are, the more your quit monkey complains. This makes intuitive sense: achieving more ambitious things is harder, so you’re more likely to fail. Being ambitious is also more likely to trigger insecurities that bring out the quit monkey.

Because of this, a surprising path to success is to be less ambitious. Instead of aiming to quit your job, aim to earn a dollar online. Instead of trying to go viral, try to get five new Twitter followers. The more attainable your goal is, the harder it is to justify giving it up. This shuts down most of quit monkey’s arguments.

It took me five years to replace my salary with income from my own products. If I had set out to quit my job in my first year, I’d have completely failed. But I set a much smaller goal: earn a single dollar.

Of course, once I earned $1, it felt possible to get to $100. And at $100, $1,000 seemed within reach. And so on. By keeping my expectations grounded at every step, I could keep setting more and more ambitious goals until one day five years later I realized I’d done it.

With products, the most attainable goal is to build something that you like. Forget customers. Forget users. Just build something that serves you and keep making it better. Because by the time you get that far, you’ll probably remember a friend of yours who has the same problem. And then you’re off to the races.

Quit and grit in practice: my latest product flop

Last month I launched an app called Community Keeper, an archive, search, and marketing tool for Slack communities. The launch went right on script: no one cared.

This got my quit monkey going, so we argued. He made some good points (“it seems like nobody wants this”), though I was able to counter some of them (“well I do…”).

Ultimately, I was still uncertain—so I lowered my expectations. I decided that Community Keeper isn’t a business that I’ll invest heavily in—at least for now. Instead, I’m going to treat it like an internal tool for me and my Slack community and see if I can make something we like.

And just like that, poof! Quit monkey disappeared. And now I’m excited about the project again.

We’ll see what happens next.

If you want to follow along my journey you can subscribe below, or follow me on Twitter.

Thanks to Rowena Luk and Wasim Lorgat for reviewing drafts of this, and to Nate Aune for the idea of representing quitting and gritting as monkeys.

Notes

-

You know, hypothetically. ↩

-

Usually—whether anyone else actually wants it, followed by how you’ll reach them if they do. ↩

-

For a longer treatment of my struggles to finish Pegasus, you can read my retrospectives from the months leading up to its launch in 2019 (Feb, March, April, and May). ↩

-

This only works well if keeping the project alive doesn’t have a substantial cost. If your project is expensive to host, takes a lot of your time to support, etc. then it’s probably better to shut it down entirely. ↩