For the last six years I’ve been building a portfolio of revenue-generating products, mostly on my own.

In that period, I’ve been almost 100% transparent about the journey. Every dollar of revenue, every hour I’ve spent, and even my strategic thinking and planning has been available from my open dashboard and monthly retrospectives.

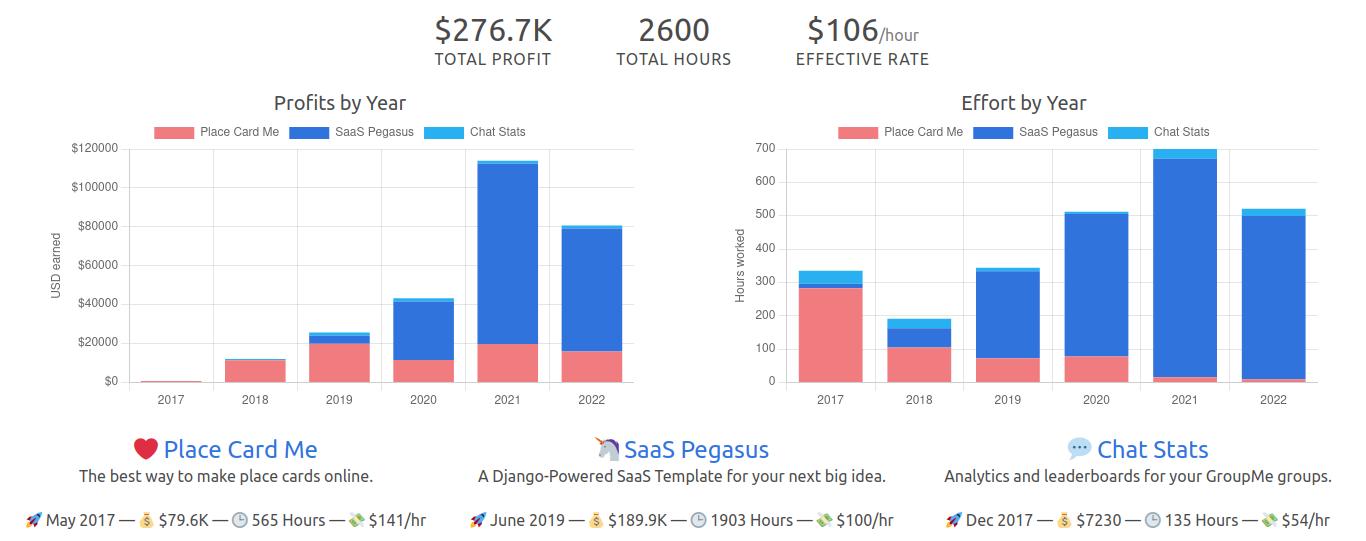

My business journey by the numbers, from the first dollar to full-time. From my open dashboard

Building in public has been good to me.

My audience—small though it is—has been a consistent source of support.

They cheer me on, give me ideas, occasionally buy or help promote my products,

and a handful have even turned into real-life friends.

It’s unclear that I’d be nearly as successful if I’d done this whole thing privately.

And it’s helped me. My retrospective process has helped me stay accountable to…myself—something

that isn’t always easy when you’re working alone.

And so it is with some reluctance that I’ve decided it’s time to stop.

Not entirely, but I’ll no longer be sharing my revenue publicly, will no longer publish monthly retrospectives,

and generally will go from being “radically transparent” to something more like “thoughtfully transparent”.

My old and new versions of “building in public”.

What follows is a reflection on why I’ve decided to make these changes.

I hope to document some of the downsides of building in public and provide a window into what

the next stage of a building-in-public journey looks like—at least for one person.

It feels like bragging

When I started building products six years ago, I had nothing but my skills and experience.

I had to claw and fight for my first dollar.

It was the hardest dollar I ever earned. And when I finally earned it, I was thrilled to shout the news from the rooftops.

Part of what made talking about that first dollar so fun was just how ridiculously cost-inefficient the whole thing was.

I calculated that my hourly rate for that dollar was half a cent.

It was so easy to celebrate because I was so obviously far from anything close to resembling a sustainable business.

I was still just a guy with a dream.

Fast forward a few years, and a lot’s changed.

My relationship with my products has gone from “fun thing I’m figuring out” to, basically, my job.

Somewhere in that transition, celebrating the revenue milestones started feeling less and less fun-and-exciting and more and more braggy-and-kind-of-obnoxious.

It’s fun being the scrappy underdog celebrating $100 a month, but as $100 became $1k and, eventually, $10k it started to feel different.

This recent Jordan Gal tweet really resonated with something I’d been struggling with as my businesses became more successful.

And it’s not just the numbers.

For many years, indie hacking was something I was doing on the side between a part-time job and freelancing.

Now it’s basically my career.

If a Google engineer came home on a Friday and Tweeted out “Check it out, I made $6k this week!” that would be ridiculous.

Was that any different than what I was doing?

And look, I’m not saying it’s bad to celebrate revenue numbers at a higher level.

People like Pieter Levels pull off celebrating making money at a scale far beyond that of my little businesses,

and he inspires thousands to follow in his footsteps.

For some of those people (including me!), that decision fundamentally changes their lives.

It’s great that Pieter Levels exists.

Pieter Levels is an inspiration for many.

But what is the line between inspiring and bragging?

Everyone will have a different answer, but for me, it’s somewhere in my past.

Fending off competitors and copycats

Competitors and copycats. Two things all successful businesses wish would just go away.

Unfortunately, the more successful you are, the worse it gets.

Both of my main products have been copied many, many times.

Sometimes people copy the idea, and add their own spin on it. I get that.

No business (including mine) doesn’t draw inspiration from something else in the world.

Other times people copy one of my businesses to an almost absurd degree.

Like, same UX, same pricing, same sections on the landing page, and so on. It’s lazy, and frankly, pathetic. And exhausting.

I would link to some, but I don’t want to give them the attention.

Links to the copycats of my products have been redacted, because screw them.

People say you shouldn’t worry about copycats—and to some extent that’s true.

They are usually lazy, don’t have original ideas, and don’t understand why or how your business works.

They can see what it is but they can’t see why it works.

In most cases a copycat will copy your app, flail around a bit, and when they fail to get traction, give up and move on. But not always. And the more you earn, the harder a copycat will work to try and dip into your profits.

There are two big problems with building in public and copycats.

The first is that it attracts them. Someone looks at your product and says “whoa, he’s making $10k a month selling that?

I could build that in a weekend.” And the more popular your “build in public” story gets, the more potential copycats you reach.

Like moths to a flame, they can’t resist being sucked in by the prospect of your sweet earnings.

The second problem with building in public—at least the way I’ve been doing it—is that

it exposes copycats and competitors to the internals of your business.

If I write in a retro that the secret sauce of my business is X then all of the sudden I’ve lost a big competitive advantage!

It probably took me months of hard work to figure out X… and they just get it for free.

As I’ve become more aware of the competition following my journey, I’ve also become more hesitant to share any details that might help them.

But those details are also the most interesting things to share!

That secret X sauce was probably the most useful thing I learned in the last month—and it’s also the exact information I don’t want to give to competition.

So now, in fighting competitors, my content is a watered-down version of itself.

Growing with my work

When I started documenting my journey I was completely clueless.

I was clueless about solo-entrepreneurship, and I was clueless about writing about it.

My cluelessness—learning every little detail in public and laughing about my silly mistakes—was

arguably a big part of the appeal of my writing.

If you were just getting started, I was relatable.

Now things are different. I don’t claim to be some entrepreneurship expert, but I’m certainly no longer a beginner.

When I have conversations with other indie hackers I usually find myself giving advice more than I receive it.

It’s easier to spot mistakes others are making—often mistakes I myself have made in the past.

My writing hasn’t grown in the same way.

To some extent I’ve clung to the idea that I’m still a bumbling idiot who doesn’t know what he’s doing.

I still try to speak to beginners, even though I no longer am one.

I’ve stagnated.

Hanging on to the idea that I should document everything publicly is a big part of that stagnation.

In the last six years I’ve published 123 retrospectives—a novel’s-length worth of content that is safe, boring, and largely useless to

improving my skill as an entrepreneur or as a writer.

Writing retrospectives has been a crutch. A way to produce content without original ideas.

A way to claim progress as a writer, while not actually progressing.

So what then?

It’s time to grow with my work.

Less documenting for the sake of documenting and more documenting because I have something interesting to say.

More bigger swings.

Probably more devastating failures.

More growth.

This writeup was the first step of the plan.

I hope it didn’t suck.

If you’re interested in more, you can subscribe below for updates, or follow me on Twitter.

Notes