In a recent post I described a feeling of uselessness associated with not working on things that felt “important” for the world—a sense that I should be working on saving the world instead of a building Django boilerplate or place card website.

A big part of the problem I was facing was a simple, yet seemingly impossible question: how to pick a cause worth working on?

Well, thankfully there’s a website for that. It’s called 80,000 Hours.1

How did this website know the exact question I was asking myself?

80,000 Hours is dedicated to helping people like me figure out how to make a difference with their careers. I’ve been consuming content on the site and in the associated podcast, and it’s been fascinating.

In this article I’ll distill some of the concepts I’ve found the most helpful. You can think of it as your cheat sheet into doing good.

Longtermism

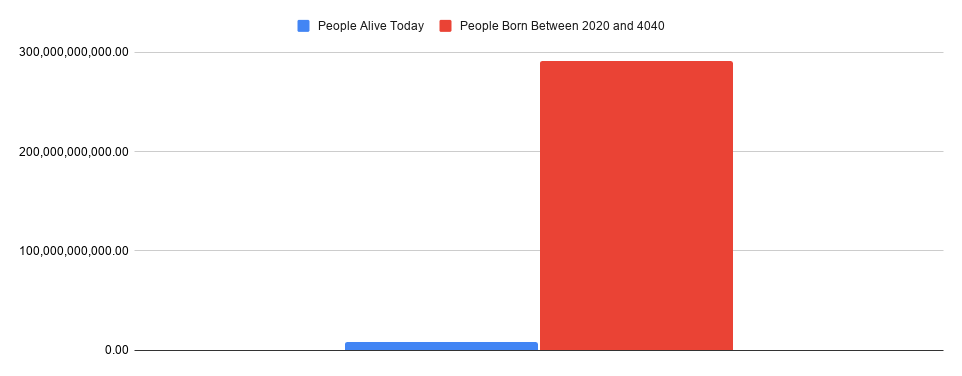

Longtermism is the position that it’s much more effective to focus on issues that affect future generations of people than it is to focus on the current population. The argument, from 80,000 Hours introduction to the topic, goes something like this:

Since the future is big, there could be far more people in the future than in the present generation. This means that if you want to help people in general, your key concern shouldn’t be to help the present generation, but to ensure that the future goes well in the long-term.

More concretely—you can imagine that humans will flourish for millenia into the future. We might expand beyond Earth, colonize other stars, galaxies, etc.

If this turns out to be true, then 99.999999% of all humans who will ever exist will exist in the future. So to help humanity—we should focus on ensuring a good future for those people and not on the tiny fraction of people who happen to be alive at the same time we are.

People alive today versus people born in the next 2020 years—arbitrarily using the current birth rate to project into the future.

If you take a longtermist perspective it becomes more difficult to justify a large amount of what today’s world would typically call “do-gooding”—namely, improving things for people who are currently alive—and instead it makes sense to focus on a much narrower set of problems: those that have an outsized impact on the future.

The most important long term problems are those that pose existential risks. That is, things which might cause humanity to wipe itself out and not achieve our future star-colonizing dreams. Possible existential problems include semi-obvious things like climate change and the potential for nuclear war, but there are also some surprising ones like AI safety that may matter a lot.

There’s a lot more nuance and depth to a longtermist approach to do-gooding—and existential risks aren’t the only place to focus2. But the core concept resonates a lot and helps put into perspective why certain causes never felt totally “right” to me.

Effective altruism

Effective altruism is a blend of economics and “do-gooding” that essentially tries to:

- Measure the cost and benefit of any particular intervention

- Weigh that cost/benefit against other possible interventions that could be done

- Choose the most cost-effective thing

It says, “if I can spend $100 to save one life, or I can spend $100 to save two lives, I should choose the latter”.

While the above seems obvious, it’s not necessarily how the world behaves.

For example, we are often more likely to support people or causes that we relate to better, and due to the uneven distribution of wealth in the world this can lead to lower unit-cost do-gooding focused on richer populations. It leads to things like NFL players wearing pink ribbons for breast cancer, even though malaria kills 10 times more people.3

But rich vs. poor isn’t the most important conclusion of effective altruism—it’s just an example. The most important conclusion is that you should invest your resources smartly.

"Weeks of coding can save you hours of planning." - Unknown

— Programming Wisdom (@CodeWisdom) May 31, 2018

Effective altruism—and particularly choosing your cause—is kind of like this software wisdom: planning leads to better outcomes.

An interesting side effect of “choosing wisely” is that spending a long time deciding what to do is worth it—because if you are able to ultimately pick something substantially more effective to work on, you’ll quickly surpass the amount of good you would have done with that time by nature of working on a better problem.4

Career strategy

Another area that 80,000 Hours focuses on is career strategy. Career strategy helps change the narrative from “what problems are important to work on?” to “what should you do?”. There are a few aspects of their take on career strategy that I found insightful.

Personal fit

The first useful concept is personal fit. That is—how good a match are you for the particular problem at hand? If effective altruism and longtermism combine to create the menu of possible do-gooding entrée’s, personal fit is the part where you look at the menu and decide what you should eat.

The most important elements of personal fit are 1) your knowledge and skills, and 2) your interests. Both of these contribute to the overall expected value of your impact, though in different ways.

With knowledge and skills it’s about your effectiveness. The more you know—or can learn quickly—in a particular field, the more effective you are likely to be in it, and the more opportunity you have to make a real contribution. Without the right knowledge and skills, you’ll spend more of your time learning and playing “catch up”.

With interest it’s more about stickiness. The more interested you are in a particular topic or field, the more likely you are to be passionate and not give up. As it is with many things, your intrinsic motivation will be the thing that eventually leads to success or failure. Optimizing for interest helps set you up to not quit.

Career capital

The second useful career concept is career capital—the skills, connections, credentials, and financial resources that can help you have a bigger impact in the future.

Why can Warren Buffett do many orders of magnitude more good than the average person? Because he spent a lifetime building up the capital to do so.

Career capital isn’t just about money. Influencers have capital in their Instagram audience, PhD’s have capital in their degrees, and everyone has capital in the skills they’ve developed and the people they’ve met in the course of their career. At a super high level, the more career capital you have, the more effectively you’ll be able to impact the world.

Career capital comes in all forms. For some, it can be your TikTok following. Photo of the Hype House.

The great thing about career capital is that it’s often translateable—you can build it up and then use it in a variety of ways. This is most obviously true in the form of money, but is also true with audiences, networks, and skills.

An interesting conclusion is that if you don’t know how to most effectively spend your time, you can use it to build up career capital, which you can then use in the future once you have a better plan.

What this means for me

First the bad news: I still have no idea how I plan to do good in the world.

The good news is: I think that’s ok!

Effective altruism tells me that this is an important decision, and that it’s good—maybe even critical—to take my time with it. Additionally, I can continue to invest in my own career capital—be it in the form of passive-income projects that free up my time in the future—or in building up my network and skills. For now there’s no reason to feel guilty about not working on the one. best. thing.5

That said, longtermism and personal fit have pointed me in one possible direction: the space of artificial intelligence research—which 80,000 Hours considers one of the world’s most pressing problems. So I’m building up some career capital there in the form of teaching myself machine learning basics and trying to figure out whether I like the work. I figure even if I end up nowhere near AI safety—having an AI / data science hammer on my toolbelt will only increase my future effectiveness in all my endeavors.

What this means for you

If you’re interested in the topic of do-gooding, I highly recommend checking out the 80,000 Hours key ideas page where you can find a more in-depth treatment of all these concepts and much more. The podcast is also good, though be prepared for a fair amount of philosophical naval-gazing. It comes with the territory.

If you got something from this article, I’d love to hear from you on twitter, in the comments, or via email.

Notes:

-

Hat tip to readers Rafael Slonik and Gaël de Mondragon who both reminded me of this site. ↩

-

For example, changing the trajectory of societal or technological development in some way is another big one, since it can have a sustained future impact. ↩

-

About 40,000 versus 400,000, worldwide, according to the American Cancer Society and the WHO, respectively. ↩

-

This is in fact how 80,000 Hours justifies its own impact on the world. By helping people like me figure out what to do they are essentially practicing effective altruism by promoting effective altruism. It’s all very meta. ↩

-

It’s possible that I’ve cherry-picked the concepts from 80,000 Hours that point me to the life I most want to lead. I don’t totally know how to safeguard against that apart from attempting to be self-aware of it. ↩